The Brightwood Papers

On Land and Legacy.

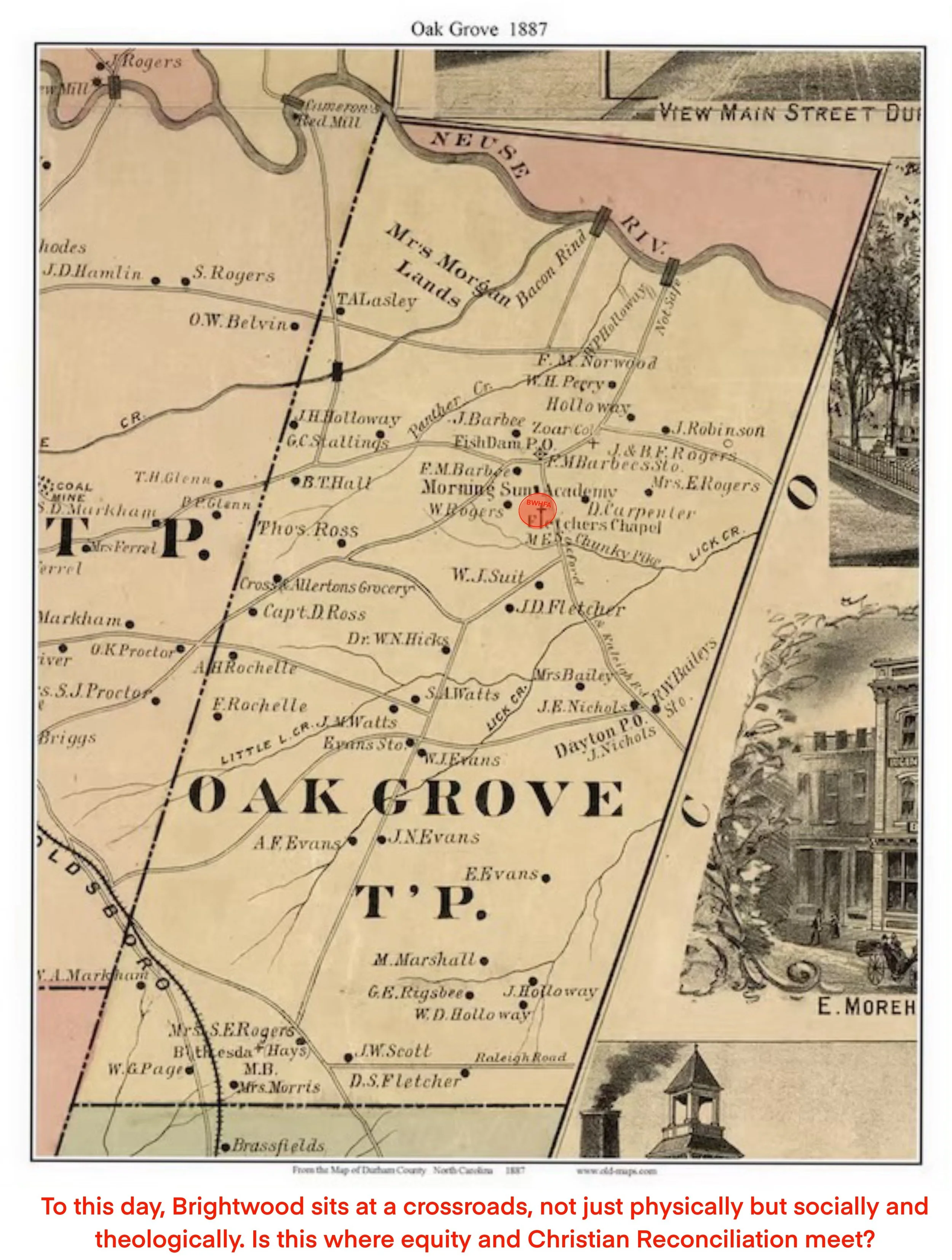

THE CROSSROADS

I.

Before Durham was Durham, this land was already common ground—though common ground, in antebellum North Carolina, was never uncomplicated.

By 1825, the crossroads at Fletcher's Chapel Road had become what crossroads become when left alone long enough: a meetinghouse, a general store, a blacksmith shop, a small Methodist congregation gathering on Wiley Fletcher's land. This wasn't plantation country. The massive Stagville complex lay nearby, built on enslaved labor and extraction, but Fletcher's Chapel represented something different—small farmers, local commerce, voluntary association. People building their own institutions rather than laboring inside someone else's.

The distinction mattered, but it wasn't innocence. The early Methodist Church held anti-slavery positions that Southern social reality slowly compromised. Enslaved people were excluded from integrated worship even as the theology preached universal salvation. The same roads that made Fletcher's Chapel a crossroads also connected it to Stagville; the same economy that sustained small farmers depended on the regional system that sustained plantations. Fletcher's Chapel was an alternative to the extractive model, not an escape from the world that model had built.

What emerged after emancipation revealed both the limits and the possibilities. Formerly enslaved people from Stagville built their own institutions—Cameron Grove Baptist Church among them—while navigating the new hierarchies of sharecropping and the old relationships that persisted in complicated forms across racial lines. The land that had been common ground for white small farmers became, slowly and incompletely, common ground in a broader sense. Not equality. Not justice. But the beginning of something that could be built upon.

That pattern was once familiar throughout the North Carolina Piedmont. Families worked land they controlled. Neighbors built churches and schools together. Wealth, such as it was, circulated locally. Most of that world is gone now, erased by suburban development that turned land into commodity and community into something you commute away from. But the road remains. The church—Fletcher's Chapel United Methodist—still stands, approaching its second century. And the land remembers what it was used for, and what it wasn't, and what it might still become.

II.

Seventy years after Fletcher's Chapel organized itself, three Black men in Durham built something on the same principle—but without the contradictions that had compromised the original.

John Merrick, Charles Spaulding, and Aaron M. Moore created the economic ecosystem along Parrish Street that would become known as Black Wall Street. Insurance companies. Banks. A network of businesses where wealth circulated through Black hands and returned to Black families. They built it under Jim Crow, in a state that had just violently overthrown the integrated government in Wilmington, in a region where Black prosperity was often answered with fire.

Durham survived where Tulsa and Wilmington burned because its white tobacco elites found tolerance more profitable than terror. The Duke family provided capital and counsel not out of justice but out of interest. Black Wall Street existed, in the end, because white power permitted it to exist.

But the model was the same model that Fletcher's Chapel had demonstrated decades earlier: people building their own institutions, wealth staying local, community forming through voluntary association rather than extractive hierarchy. Parrish Street was the urban expression of something already proven in the rural Piedmont—only this time, built by the people whose labor and exclusion had subsidized the original. Different context, same logic, more honest foundation. Control the land, build the institutions, keep the wealth circulating among your own.

The difference was protection. Fletcher's Chapel had geography—rural, dispersed, beneath notice. Parrish Street had political calculation—white elites who saw Black prosperity as useful. Neither had permanence. Both existed at someone else's pleasure.

I've spent years sitting with what that means.

III.

Spence and Minnie Suitt farmed the land at Fletcher's Chapel Road in the early twentieth century, part of the continuity of agricultural use that characterized the area for generations. A century later, I ran a homestead on the same soil.

For five years, I taught regenerative agriculture on three and a half acres in Durham County. Families learned to grow their own food. The land became a classroom, a research hub, a gathering place where economic barriers dissolved through shared cultivation. It was the Fletcher's Chapel model translated into contemporary practice—common ground, local production, voluntary community—but this time without the exclusions that had haunted the original. The land that had once been common ground only for some was becoming common ground for real.

But I kept watching the same families return each season with the same problem. They had food. They had skills. They had community. What they didn't have was stable ground beneath them. Rent kept rising. Landlords kept selling. Neighborhoods kept "revitalizing" in ways that meant the people who'd lived there longest could no longer afford to stay.

Food security without housing security is just a nicer waiting room for displacement. You cannot cultivate wealth from land you do not control. The Suitts knew that. The Triumvirate knew that. The formerly enslaved families who built Cameron Grove knew it most painfully of all—freedom without land tenure is conditional freedom. I learned it by watching families scatter.

So I learned a new language: covenants, zoning law, lender negotiations, the slow machinery of how land actually gets held and developed. The same instincts that worked in the garden—patience, stewardship, thinking in generations—turned out to work for housing. The homestead didn't end. It became the foundation for what comes next.

IV.

What we're building now is not new. It's a restoration—and a completion.

The Community Land Trust model does what Fletcher's Chapel did in 1825 and Parrish Street did in 1898: it creates common ground where wealth can circulate locally and community can form across property lines. Land held in permanent trust cannot be sold to speculators when the neighborhood gets hot. Equity structured as shared ownership cannot be extracted by outside capital. Families can build wealth across generations without the threat of displacement.

But the CLT also corrects what those earlier models got wrong or couldn't control. Fletcher's Chapel was common ground with asterisks—available to some, maintained by the exclusion of others. Parrish Street was common ground under surveillance—tolerated as long as white power found it convenient. The Brightwood Community Land Trust is designed to be common ground without conditions. Not protected by geography. Not protected by political calculation. Protected by legal structure, by covenant, by the simple fact that you cannot buy what is not for sale.

Durham in 2025 has conditions that make this possible: progressive land use policy, legal frameworks for CLTs written into the Unified Development Ordinance, impact investors who understand that permanent affordability is the investment. The protection that was once personal—dependent on the goodwill of benefactors or the indifference of those in power—has been institutionalized. That's not foolproof. Policy can change. But it's more resilient than the tolerance of tobacco magnates or the invisibility of rural crossroads.

I've learned from history what Fletcher's Chapel and Parrish Street couldn't teach: how to build what cannot be taken, and how to build it for everyone.

V.

The land at Fletcher's Chapel Road has witnessed two centuries of American social evolution—slavery and emancipation, Jim Crow and civil rights, agricultural economy and suburban sprawl, extraction and resistance. The same roads that once carried enslaved people to Stagville's fields later carried their descendants to churches and schools they'd built themselves. The same crossroads where white farmers traded goods became, over generations, a place where the full complexity of Southern history played out in daily encounters, uneasy accommodations, and slow expansions of who counted as neighbor.

Cameron Grove Baptist Church emerged from Stagville after emancipation—formerly enslaved people building their own institutions when finally given the chance. That pattern repeats throughout this landscape. Given even partial access to common ground, people build. Given land they can hold, communities form. The impulse is older than any of the systems designed to suppress it.

Brightwood sits in that inheritance. Not just the inheritance of Black Wall Street, though that legacy matters. The older inheritance too: land that was already being used for community-centered development before Durham existed, before the railroads came, before tobacco money built mansions and required the labor that built those mansions. And the inheritance of those who were excluded from the original common ground but built their own anyway, in the margins, after emancipation, against opposition.

The extractive model is the aberration, not the norm. For most of human history, land was held by people who worked it, shared it, built institutions on it together. Speculation and displacement are recent inventions. The CLT isn't radical. It's a return to how land functioned before we financialized it—and an extension of that function to people who were locked out the first time around.

I'm not starting something new. I'm continuing something that got interrupted, and I'm trying to do it right this time.

VI.

People ask why I moved from gardening to housing, and I tell them I didn't move at all. The work is the same work. You prepare the ground. You plant with intention. You tend with patience. You harvest collectively. You pass the land to the next generation in better condition than you found it.

The crop is different. The principles are identical.

Merrick, Spaulding, and Moore are remembered as great men, and they were. But what made them consequential wasn't personal greatness—it was the institutions they built, the systems they left behind, the infrastructure that kept working after they were gone. A century later, we're still drawing on their account. That's the only measure that matters: not what we accomplish in our own lifetimes, but what remains when we're no longer here to maintain it.

Fletcher's Chapel has lasted two hundred years because a congregation kept showing up. The land at Fletcher's Chapel Road has been worked continuously since the Suitts farmed it a century ago. Cameron Grove still stands because formerly enslaved people decided their freedom required institutions of their own. Continuity is its own kind of resistance. Persistence is its own kind of power.

The Brightwood Community Land Trust is my attempt to build something that lasts like that. Not a moment, but a structure. Not a protest, but a foundation. Common ground—truly common this time, without the asterisks—permanently held, for whoever comes next.

The land holds memory. All of it: the small farmers and the enslaved people who worked nearby, the Methodist congregations and the Black churches that formed after emancipation, the Suitts farming a century ago and the families learning to grow food today. The community holds vision—not nostalgia for an innocent past that never existed, but clear sight about what worked, what failed, and what can be built now that couldn't be built before.

And the trust—the legal structure, the permanent covenant, the ground held in common—holds both for as long as any of us can see.

The work continues. That's all there is to say, really. The work continues.

Skip Gibbs Founder & Executive Trustee Land and Legacy Group Durham, North Carolina